Featured

For Black Americans, Dealing With Mental Illness Has Always Been Complicated

“Byron, I think I’m gon’ kill myself.”

What is a 12-year-old to do when he hears his aunt say that?

Yet, kids, adults, anyone who would listen to Aunt Geraldine became accustomed to hearing her contemplate ending her life, usually as she chain-smoked Kool Menthol cigarettes.

In the 1970s our family was like other families with relatives dealing with mental illness. Many of our people talk about the “crazy” uncle in the attic or the relative in the back room who didn’t come out much. Growing up, undiagnosed mental illness was all around me. But Aunt Geraldine’s illness was the most pronounced. She once looked like a Hollywood starlet, smart enough to earn a teaching degree and brave enough to move to Indiana to fulfill her hopes and dreams. A few years later, she returned to her North Louisiana hometown as a different, broken person.

May is Mental Health Awareness Month, when a needed light is cast on mental illness. Those who have not dealt with a friend, loved one or relative suffering from mental illness might consider themselves lucky. Statistics say that one-fifth of Americans will experience a mental illness. And 4% of Americans live with a serious mental illness.

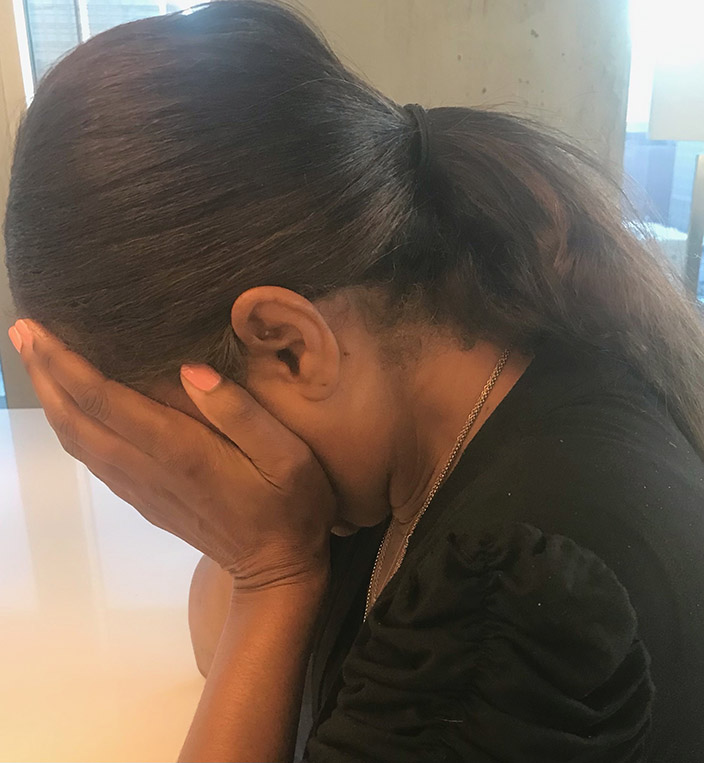

For Black Americans, treating mental illness can be complex. Our tradition relies on faith to carry us through and sometimes alcohol and drugs to cope. Getting past old stigmas are tough, too. Often families keep quiet.

These days, they should not have to.

Dr. Ashaki Warren, a child and adolescent psychiatrist based in Atlanta, is a leading voice in helping to demystify mental illness.

“I view mental illness recovery the same way as treatment of other medical conditions such as diabetes, cancer or heart disease,” Warren said. “We accept that there is not always an instant cure, and the new reality for mental illness may be learning how to support people in their current situation. No matter how insurmountable the odds may seem initially, as a society we relentlessly advocate for treatment. We do this because we have seen this lead to a better quality of life for many patients and their families.”

While rates of mental illness for Black people are generally in line with that of the general population, one-third of us who need mental health treatment do not get it. That’s according to a 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Yet, the survey reports 4.5 million (16 percent) Black and African American people as having a mental illness.

—

Over the years, we all watched Aunt Geraldine struggle. No one in the family was equipped to handle this journey. She was admitted and discharged from the mental ward at our local public hospital, known colloquially as “The 10th Floor.” She never seemed to improve. She walked the streets of our town wearing the same clothes everyday. She smoked. She attempted to drown herself in a muddy pond on our property. She shot herself in the head with a pistol once, but the bullet skimmed her scalp. She attempted to shoot herself again in front of her nieces and nephews before an adult wrestled a gun out of her hand.

One day her suffering ended. She laid on the railroad tracks behind her mother’s house and died under the wheels of a Southern Pacific train. She was in her mid-50s.

All of the obstructions to getting good mental health care were overwhelmingly apparent back then, much as they are today for minorities. According to the American Psychiatric Association, they include:

- Mental illness stigma.

- Lack of insurance, underinsurance

- Lack of diversity among mental health care providers

- Lack of culturally competent providers

While society is more open-minded about mental health today, our community still faces an uphill climb for better overall mental health care. Even so, I’m certain that today’s medicine and a more understanding society might have saved Aunt Geraldine.

That’s progress worth noting.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please call 1-800-273-8255.

Byron McCauley is a veteran journalist and communications executive based in Cincinnati, Ohio. He is the co-author of “Hope, Interrupted: America Lost and Found in Letters (hopeinterrupted.com).” Email him at info@mccauleycommunications.com.

-

Black History5 months ago

Black History5 months agoThe untold story of a Black woman who founded an Alabama hospital during Jim Crow

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months ago‘No Closure’ In Town Where Five Black Residents Were Either Murdered, Died Suspiciously Or Are Missing

-

Black History9 months ago

Black History9 months agoBlack History Lost and Found: New Research Pieces Together the Life of Prominent Texas Surgeon and Activist

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoFounder of “The Folding Chair” Podcast Calls Montgomery’s Brawl ‘Karma’

-

Featured8 months ago

Featured8 months agoThousands ‘Live Their Dream’ During National Black Business Month

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoJuneteenth And ‘246 Years Of Free Labor’ Are Key To Conversations About Reparations