Featured

How The Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike Addressed Labor And Civil Rights

One of the most famous efforts to acknowledge the value of Black employees and their civil rights started in February 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. The city’s sanitation department which employed large numbers of African Americans had a bad reputation because of its unhealthy working conditions. Disgruntled workers were moved to action when two sanitation workers died on the job when a malfunctioning truck crushed them.

Kiereka King’s grandfather was a sanitation worker in 1968.

“People [in some neighborhoods] would let their dogs attack them,” she recalled.

The 26 year-old’s grandfather died shortly before former President Barack Obama took office in 2008. Edward Johnson, Sr. quit school in the third grade to help his father who was a sharecropper in Tennessee. He eventually moved to Memphis and met his wife, King’s grandmother. Together they had 15 children.

“My grandfather was not much of a talker about the things he went through,” King said.

But he did discuss the sanitation strike which began on Feb. 12, 1968. The strike drew Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King to town as 1,300 workers participated in a work stoppage. They wanted a pay increase from the 65 cents they earned per hour, and they also demanded better and safer equipment.

According to the King Center at Stanford, the strike had a successful kickoff, and the City Council acknowledged the sanitation workers union and supported raises. But the mayor did not agree to the concessions and peaceful protesters were confronted with tear gas on Feb. 23.

Dr. King supported the union, saying “all labor has dignity.”

But the job was a tough one. Some city residents refused to even bag their trash.

“[They would] leave it filthy for them to clean up … to even throw it on the truck,” King said her grandfather once explained.

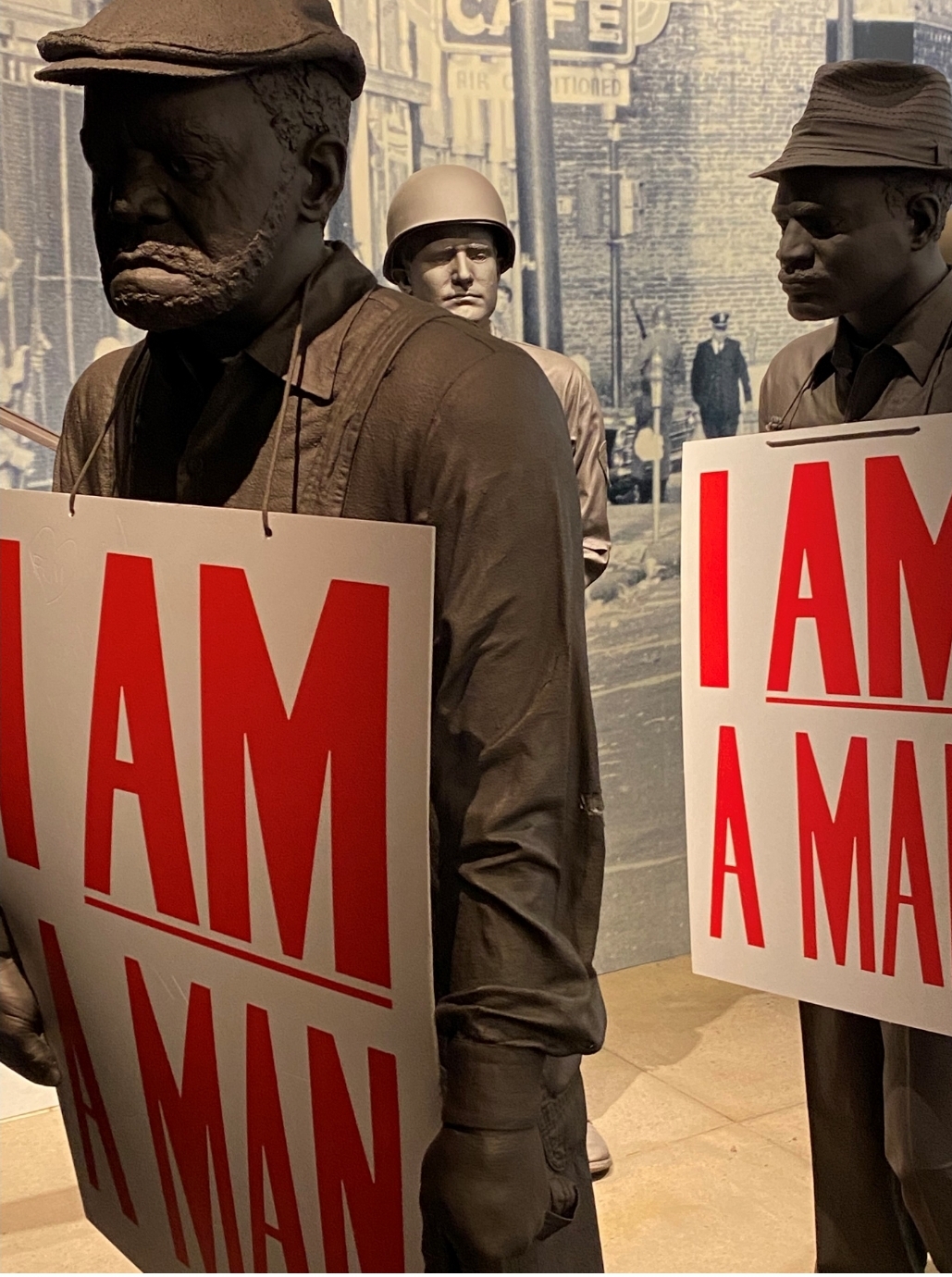

The Black community in Memphis stood with the workers, and so did King who traveled to Memphis in March. The mayor and police attempted to break the strike and used violence to intimidate the men. King returned on March 28 to lead a march through downtown Memphis. He was joined by 6,000 people and the sanitation workers wore the now-famous “I Am A Man” placards for the first time.

On April 3, King returned to Memphis in an ongoing show of support for the sanitation workers. He delivered a speech that night, which would tragically become his last, at Mason’s Temple. The following evening King was assassinated as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

After the assassination, President Lyndon B. Johnson sent James Reynolds, undersecretary of Labor, to Memphis to resolve the strike. Less than two weeks later, on April 16, the strike ended with the city agreeing to issue raises to African American workers and recognize the workers’ union.

-

Black History5 months ago

Black History5 months agoThe untold story of a Black woman who founded an Alabama hospital during Jim Crow

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months ago‘No Closure’ In Town Where Five Black Residents Were Either Murdered, Died Suspiciously Or Are Missing

-

Black History9 months ago

Black History9 months agoBlack History Lost and Found: New Research Pieces Together the Life of Prominent Texas Surgeon and Activist

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoFounder of “The Folding Chair” Podcast Calls Montgomery’s Brawl ‘Karma’

-

Featured8 months ago

Featured8 months agoThousands ‘Live Their Dream’ During National Black Business Month

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoJuneteenth And ‘246 Years Of Free Labor’ Are Key To Conversations About Reparations