Featured

Members of the Central Park Five Say There is Power through Perseverance

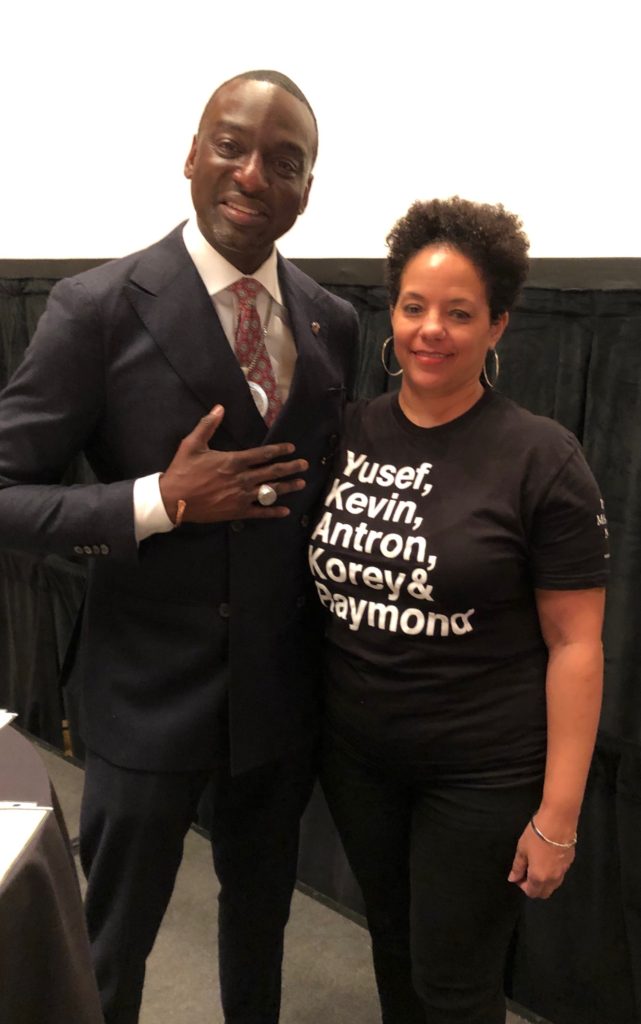

When Lisa Shelton first saw them she wanted to cry. She thought about the miniseries and what it was like for them to be trapped behind bars for so many years for a crime they didn’t commit. Then she saw them smile.

“I was amazed,” Shelton said. “Their spirit is so vibrant.”

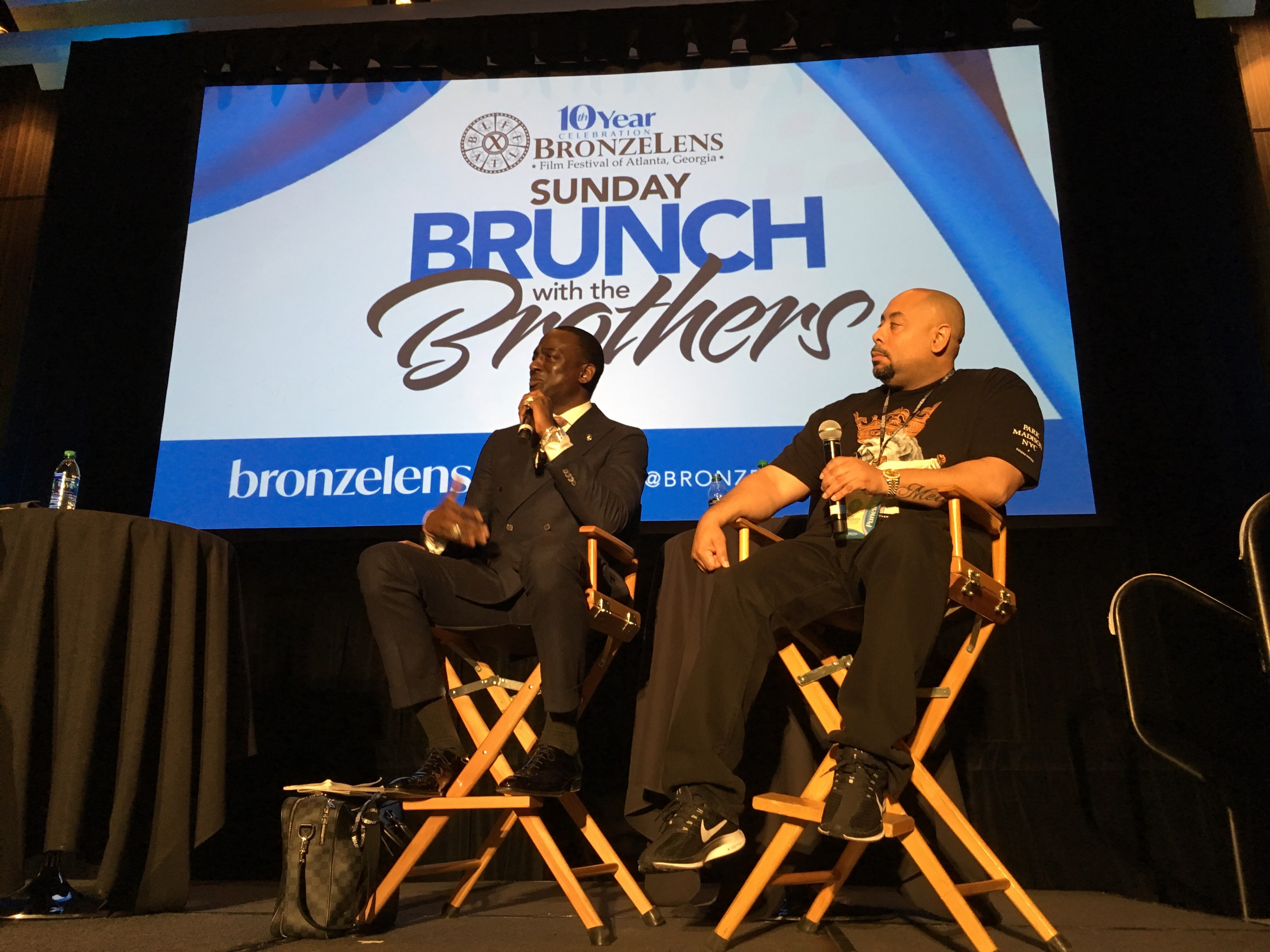

Perhaps that was the main takeaway for Yusef Salaam and Raymond Santana, Jr. as they shared their stories amidst awe and applause Sunday at the 10th anniversary of the BronzeLens Film Festival in Atlanta.

Salaam and Santana were members of the Central Park Five as they were called after the April 19, 1989 crime in which a jogger was brutally beaten and raped in Central Park. Then 14 and 15-year-old teenagers, they were among the five African Americans and one Hispanic teenager who were wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for the crime. The other three were: Korey Wise, then 16, Antron McCray, then 15, and Kevin Richardson, then 14.

Their stories were first captured and told in a 2012 documentary, The Central Park Five and recently retold in in Ava Duvernay’s four-part miniseries, When They See Us.

“When you see the doc, you see these five kids who found out that they have a voice and now when you see the series, we’re using our voice,” Santana said. “We’re grown now. You see the growth and development.

Interestingly, they never knew each other’s story until they saw it portrayed in depth in the miniseries.

“We didn’t know about the fullness of the story, we just knew loosely about it,” Salaam said. “People who return from prison usually never talk about whatever happened inside or whatever their situation was like. That’s just like a known thing.”

So, Salaam added “I had never heard Raymond’s story. I had never heard Kevin’s Story. I had never heard Antwan’s story. Definitely didn’t hear Korey’s story. We just kinda thought, my experience was like everybody else’s experience and everybody’s experience was the same.”

But their stories had variations and one character’s story would be seen as more heart wrenching than the others. Still, within their collective stories, there was a message.

“We were finding out that we each had what would be considered superpowers,” Salaam said. “The spike wheels of justice ran us over and we’re still here. They threw us down and put dirt on our birth. And we emerged like the Phoenix. We were diamonds, hardened into these beautiful things.”

The Push to Prison

Described as one of the most widely publicized crimes of the 1980s, more than 400 articles were written about the case within two weeks of the crime. Those articles dissected the lives of the teens. They were painted as terrorists.

“He placed a bounty on our heads,” Wise reportedly said. Salaam saw it as a nod to society: “They could do to us what they had done to Emmett Till.”

He said others followed, calling for them to be hanged, stripped naked and whipped. Hate mails and death threats came through the mail.

“They were trying to make us hide in plain sight,” Salaam said. “In a similar way to now when we see all of the police brutality that is going on. Everything that happens in our communities is trying to make us live in fear.”

They were charged as adults but sentenced as juveniles. “So, we received the first strike,” Santana said. “And that was all due to the media.”

There was no evidence. None of their DNAs matched the two semen samples collected at the scene. But the media cast them as guilty and they became society’s most hated.

“It put the fear into people and what it did, it made them ignore all that (lack of evidence),” Santana said. “It made them say, ‘Well they said they did it, so they must be guilty.’ And by society turning their back on us, they let the system do whatever it wanted to do with us.”

The five were prosecuted based primarily on confessions made after hours of police interrogation without the benefit of attorneys. Within weeks they withdrew their confessions and pleaded not guilty. But it didn’t matter. They lost at trial.

“It was a case where they were trying to build on the fears of the public,” Salaam said. “Young black and brown people are capable of the most heinous things and so therefore we need to treat them with these new laws we want to roll out.”

Santana said their case led to the 1994 Crime Bill, and the changing of the juvenile laws in several states. For Salaam it was part of a hidden truth.

“I found out about the 13th Amendment when I went to prison. Never even knew that there was a clause in the founding documents of this country that say we can turn you back into a slave for the punishment of a crime,” Salaam said. “We were given a mark saying, ‘We need this person to be as ignorant as possible and we need to arrest their thinking, their minds everything so that they can just be a slave.’”

Though slavery was said to be abolished, Salaam saw something different on television.

“I see what looks and appears to be slave catchers arresting us and if we happen to be black and brown people being arrested most often, we’re being arrested after we’ve been shot,” Salaam said. “So, if you have the complexion for acceptance, you can shoot up a church and they’ll take you to go get dinner. But if you have the complexion for rejection, you could be sitting in a car reading a book and lose your life. You could be Trayvon Martin. You could be countless of others that could be known and unknown.”

Finding the Path to Restoration

After serving six to seven years in prison, four of the five were released. But they would discover more barriers to their path to restoration.

“It wasn’t just a prison sentence, it was a social death,” Santana said. “We wasn’t supposed to survive prison and then when we came home we wasn’t supposed to survive socially.”

When they came back, they had a 7 p.m. curfew. They had to register as a sex offender and they had to attend sex offender meetings.

“So, it was extremely difficult when you think that you have the tools and then now you have these new set of rules that just blindside and hit you,” Santana said.

He filled out several job applications, but once they discovered he was convicted of the Central Park jogger rape, it was over.

For them, there were no transition houses, no programs to help them reenter society.

“We were just dropped off, ‘Go fend for yourself,’” Santana said.

“Not only fend for yourself,” Salaam added. “But we’ll see you later with the modern-day Emoji wink.” He knew what they were saying: “You’ll be back, six months to a year.”

But they didn’t give up searching and then they found their voice.

“One of the cool things about it is as well is that for years we were like ‘Damn we need our voices back,’” Salaam said. And they found it through Duvernay’s series.

But first there was the 2012 documentary.

Before he had a chance to tell her, Santana’s then eight-year-old daughter had already heard about the Central Park Five. She could summarize the case thanks to YouTube. But there was one thing his daughter didn’t know until she watched the documentary with him at IFC Center in New York.

After it was over, “Come closer,” she said, indicating for him to bend over so she could whisper in his ear.

“Why?”

“Come closer,” she insisted. Santana bent over.

“I didn’t know you were one of the Central Park Five.”

“Who did you think I was?”

The child shrugged, “An executive producer.” Later, she had more to say. Though her father was her hero, the person she felt sorry for the most was Wise.

It was a sentiment shared by many.

“It was heart wrenching to see how devastating his story was,” Salaam said.

When Salaam was brought in for questioning, Wise showed up for support. But he was pulled into the interrogation room. Questioned without the supervision of an adult, Wise was coerced into making a false confession.

He was tried as an adult and sentenced to five to 15 years in an adult prison while the other four were tried as minors and sentenced to five to 10 years in a youth correctional facility. The teen was thrown in amongst hardened adults, endured a lot of violence and abuse at Rikers Island in New York and in other federal prisons. He also spent hours locked away in solitary confinement.

But he never broke.

“Korey is magic,” Salaam said. “Korey is a mythical, magical person that survived this thing that really killed him.”

As, he told them, “This is life after death,” Salaam recalled. “’The Korey you knew in 1989, that Korey Wise that was surviving through this whole prison industrial complex, the belly of the beast. That Korey is dead. This is the new Korey that is fighting for the other Koreys just like me who didn’t have a person like me to fight for them now.’”

To Salaam, he was like a sage.

“The part of the series that got me was when they came to get Korey for one of his parole hearings. He’s doing pushups and they’re coming to get him and all along you could see he was being worn down and beat up.”

Then he decided. “Like ‘Damn, they’re not hearing me. I didn’t do this.’ And finally, he just said, you know what, ‘if they don’t want to hear my truth, I don’t want to waste my time.’”

And then, “He became magic again,” Salaam said. “By being where he was, meeting the guy who really did it.”

Salaam left it to Civil Rights Attorney Mawuli Davis, who hosted the question and answer session, to summarize what happened.

“When they’re out on the yard and he meets him and when Matias Reyes goes to reach to him,” Davis said. It could have ended there. “But instead, as you said, ‘magical.’ His spirit was still open even after they had a physical altercation, ‘Ahh man it’s squashed’ and that may have freed Reyes to say, ‘Let me just come forward now.’”

Reyes confessed to being the lone perpetrator in the rape. Unlike the five, his DNA and knowledge of the crime confirmed his guilt and in 2002, Wise was released from prison after serving 13 years.

In 2003, the five sued the city of New York for malicious prosecution, racial discrimination and emotional distress. It took them 11 years to win the battle. They were awarded $41 million.

Now they share their stories with everyone who will listen. But their main targets are the young.

“We see it as a vehicle that they can put in their tool kits and say, ‘Never again will there be a Central Park Five,’” Salaam said. He wants them to learn through their story how to fight the system.

He wants them to see, “That we’ve got comeback power,” Salaam said. “But you have to make sure you land on your back. Cause as they say, ‘If you can look up, you can get up.’”

Santana, who has since created his own world-renown line of T-shirts, sees the uphill struggle. Black and brown children are more valuable ignorant and behind bars.

“The system, if they get them young enough, can make upwards of $250,000 off them,” he said. “That’s the reality. There is a war and they after our cream, which is the most important part and that’s our children.”

Salaam, an inspirational speaker with Creative Artists Agency (CAA) in Los Angeles, is reminded of what someone said, “’ least educated you are, the more you’re worth; the more valuable you are to society.’”

But he and the others have another message:

“We’re trying to tell everybody go free,” Salaam said. “We’re trying to tell everybody that when you’re going through something, you’re not the first person that went through it and you’re not going to be the last person that went through it; but persevere. When you’re walking through hell, keep on walking.”

-

Black History5 months ago

Black History5 months agoThe untold story of a Black woman who founded an Alabama hospital during Jim Crow

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months ago‘No Closure’ In Town Where Five Black Residents Were Either Murdered, Died Suspiciously Or Are Missing

-

Black History10 months ago

Black History10 months agoBlack History Lost and Found: New Research Pieces Together the Life of Prominent Texas Surgeon and Activist

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoFounder of “The Folding Chair” Podcast Calls Montgomery’s Brawl ‘Karma’

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoThousands ‘Live Their Dream’ During National Black Business Month

-

Featured11 months ago

Featured11 months agoJuneteenth And ‘246 Years Of Free Labor’ Are Key To Conversations About Reparations