Culture

Secrets of the Mighty Mississippi

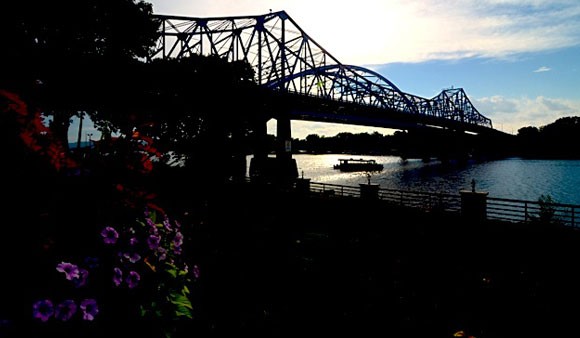

Travel the Mississippi River through western Wisconsin today, and you’ll meander past small towns that seem barely touched by the passing of time.

Life moves at a slower pace here. Diesel-powered towboats strain against massive barges that can be up to two miles long, transporting an average of 15 million tons of cargo per year. Freight trains – as many as 85 per day – provide a near-constant soundtrack, their haunting whistles echoing off the river bluffs.

For untold numbers of enslaved 19th-century African-Americans, the river represented freedom, an important route on the Underground Railroad.

“As far as the Underground Railroad was concerned, they needed to get the escaping slaves to Canada, because of the Fugitive Slave law,” explains Errol Kindschy, a retired history teacher who lives in West Salem, Wisconsin.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 proclaimed that captured runaway slaves must be returned to their masters, even if they had been caught in states that had abolished slavery, so passage to Canada – where the law didn’t apply – was highly desirable for many slaves.

“They had to get to Canada in order to be free,” Kindschy continues. “And of course they traveled only at night, so therefore during the day they were sleeping or trying to stay quiet. When they were traveling, basically they were traveling incognito, or in wagons with straw around them.”

Once they reached the safety of the free states (although the term “free” is relative, given the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Act) they’d often transfer to boats to continue their journey north.

Kindschy doesn’t have definitive proof, but town folklore holds that his home in West Salem, built in 1859, provided shelter on the Underground Railroad.

“There was a full basement. But not under the kitchen, which was attached to the house,” he says. “So therefore, I was told, is where Thomas Leonard [the founder of West Salem and the builder of Kindschy’s home] had a secret passageway behind the kitchen stove and dug out underneath the kitchen, where there was no basement, as a hiding place.”

Unfortunately, later owners remodeled the home, expanding the basement and destroying the secret passageway, but Kindschy says local residents, now in their 80s, remember playing there as children, pretending to be runaway slaves.

Kindschy also relates another fascinating piece of the area’s African-American history. In 1864, an escaped slave from Tennessee by the name of Nathan Smith settled here on a plot of farmland that came to be known as Nathan Hill (and as late as the 1960s the N-word was often appended as a prefix to that name).

According to Kindschy, Smith was an engaging character who made friends quite easily with the locals. “He’d sit out on the porch when he got through with his chores,” Kindschy says. “He raised watermelons and other crops. He’d be out there with his banjo, and he’d be singing, and a lot of times people would stop and talk to him, and they’d also sing with him, and he was quite a character.”

A sign marks Nathan Hill today, although a future highway-widening project might threaten the site’s preservation.

Another intriguing chapter in Nathan Smith’s story involves one of his adopted children.

Kindschy says, “Since they had no children, he took children in, including a white child. But the child, of all the children, that interests me, is George Taylor. Because George Taylor was the first black man to run for president of the United States. It was not Obama. It was George Taylor, and the year was 1904, and he ran against Teddy Roosevelt [as the candidate of the National Liberty Party].”

According to historical accounts, Taylor received only a handful of votes, leaving politics afterwards to become a newspaper editor and director of an African-American YMCA branch in Jacksonville, Florida where he passed away in 1925.

Nathan Smith passed away at his home in West Salem in 1905 and was buried in the city’s Hamilton Cemetery. His tombstone is worn, but still legible, serving as a reminder of an often-overlooked part of Wisconsin’s African-American history.

Tune in to “TheVillage Celebration,” airing on Soul of the South Network in February 2014 for more details of Glen Abbott’s travels on Wisconsin’s Great River Road [check local listings for channel and show times].

-

Black History5 months ago

Black History5 months agoThe untold story of a Black woman who founded an Alabama hospital during Jim Crow

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months ago‘No Closure’ In Town Where Five Black Residents Were Either Murdered, Died Suspiciously Or Are Missing

-

Black History9 months ago

Black History9 months agoBlack History Lost and Found: New Research Pieces Together the Life of Prominent Texas Surgeon and Activist

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoFounder of “The Folding Chair” Podcast Calls Montgomery’s Brawl ‘Karma’

-

Featured8 months ago

Featured8 months agoThousands ‘Live Their Dream’ During National Black Business Month

-

Featured10 months ago

Featured10 months agoJuneteenth And ‘246 Years Of Free Labor’ Are Key To Conversations About Reparations