Culture

Washington Park: A Century of Memories, a Monument to Black History

During the decades when Black people were being suppressed and subjugated by racist laws, many fought to carve out their own place in a segregated society. The results were black-owned businesses, churches and clubs. Some led the way to establish their own neighborhoods, organizations and newspapers. They built their own banks, schools and parks. And these became legacies of their fight and their success. But many of these legacies have been neglected and forgotten. TheVillageCelebration’s series for Black History Month 2020 will look at some of these abandoned legacies.

For 60 years, Patricia Gartrell has called Atlanta’s Washington Park neighborhood home.

Gartrell said her family moved to the neighborhood because her mom always wanted to live on the westside. Still, they weren’t the only ones who wanted to move to the first planned Black suburb in the City of Atlanta.

Developed by local businessman and entrepreneur Heman E. Perry, the neighborhood was established in 1919 and became home to some of the city’s most influential community leaders, Black-owned businesses and institutions.

And at the heart of the neighborhood was Washington Park, which recently celebrated its centennial.

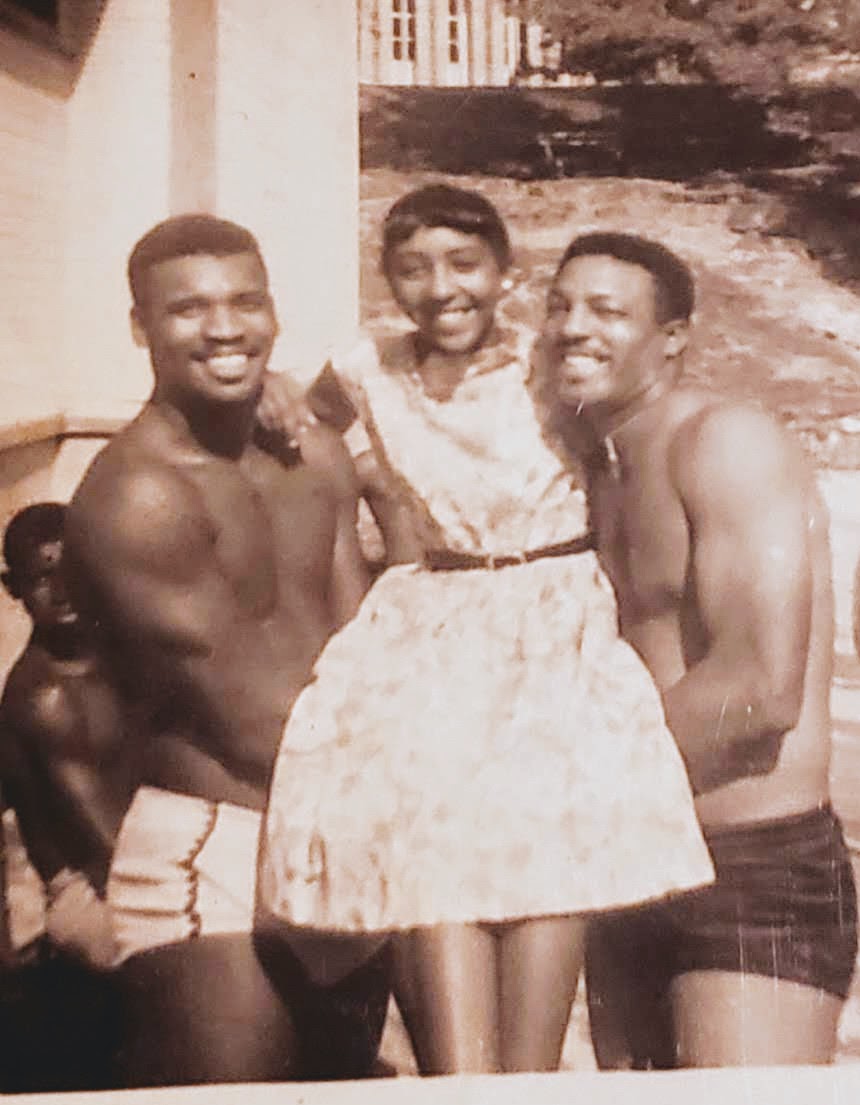

“We always had our own park. Things were safe, we could walk to the park and our parents didn’t have to worry about us,” Gartrell said. “I learned to swim at Washington Park. There was a playground, swings, it was fun.”

In 1919, Washington Park was donated as the first recreational greenspace for African Americans in Atlanta. Perry, one of the city’s first Black millionaires, donated 6.57 acres of land to the city of Atlanta to build a swimming pool for Blacks.

Progress & Possibility

The park has since grown to 25 acres with added amenities such as a tennis center, conference room and a natatorium. Black families would travel from across the state to visit the park on Ollie Street. They held picnics, played baseball and pushed their children on the swings on the piece of land they could call their own. They held meetings in the conference room, parties at the pavilions and hosted carnivals.

“People were known to take a bus to come in, even if it was to recreate for an hour,” said Cj Jackson, chair of the Conservancy at Historic Washington Park, a non-profit organization established to preserve the history of the park and to advocate on behalf of the residents and the neighborhood.

The park was a central part of their lives. It welcomed the state’s black residents and offered them a place for recreation during the Jim Crow era.

“Prior to 1919, black citizens of Atlanta had to prove they worked for whites if they were found in the park,” Jackson said. “It was a place for folks to just be human and have all their needs met.”

It was a place for the working class as well as college presidents. The Atlanta Daily World, one of the city’s first black-owned newspaper, hosted annual picnics at the park.

It was a safe place for black people to flourish, Jackson said. “It created the foundation for the formation of the black middle class in Atlanta.”

And it involved a landmark decision.

Reviving the Park

“It was the first time the city of Atlanta told white people that they had to leave an area,” Jackson said. “It broke the color line. White people moved further into the West End. They had to leave the park.”

But then everything changed. And the park, which was once the playground of up and coming Black leaders such as Martin Luther King and Maynard Jackson, the city’s first Black mayor, became a center of criminal activities. The numbers of visitors dwindled, the facilities fell into disrepair and many of the residents began moving away.

“As I got older, and the older generation was starting to die out, I could see the young people starting to move out and leaving the homes that their parents had paid for. And things started to go down,” Gartrell said. But she and a few others have continued to hold on.

“The existence of this park has meant everything to me,” Gartrell said. “My kids played in the park. Now I have grandkids who have grown up in the park.”

Jackson said the decline began in the 1970s with economic expansion and the broadening of the MARTA rail line service to go under Washington Park. Full integration had arrived.

“Looking at the face of it, it’s debatable whether full integration has been a benefit for black people in major cities,” said Jackson who began chairing the Conservancy in 2007.

Still, she understands “caring about the park has to come from our own,” Jackson said. “The challenge is to get folks that use the park to take care of it.”

Through fundraisers, the help of volunteers and partnerships with the city, businesses and organizations, Jackson is fighting to preserve the park, which in 2000 was declared an historic landmark.

Jackson wants black residents to understand it’s their job to help steward the park into the future. She wants them to understand its value.

“At the end of the day, if people don’t cherish what have been built for them, they will lose it,” she said.

For more information on preserving the park, visit www.conservancyathwp.org.

-

Black History5 months ago

Black History5 months agoThe untold story of a Black woman who founded an Alabama hospital during Jim Crow

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months ago‘No Closure’ In Town Where Five Black Residents Were Either Murdered, Died Suspiciously Or Are Missing

-

Black History10 months ago

Black History10 months agoBlack History Lost and Found: New Research Pieces Together the Life of Prominent Texas Surgeon and Activist

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoFounder of “The Folding Chair” Podcast Calls Montgomery’s Brawl ‘Karma’

-

Featured9 months ago

Featured9 months agoThousands ‘Live Their Dream’ During National Black Business Month

-

Featured11 months ago

Featured11 months agoJuneteenth And ‘246 Years Of Free Labor’ Are Key To Conversations About Reparations